Northern European Art of the Renaissance Generally Avoided Detail and Texture

Welcome to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries in Northern Europe, the era of New Art or ars nova . What was new in this era? Plenty! Artists were examining the physical world in a style that earlier artists, who focused on the spiritual world, did non.

Jan van Eyck, Madonna with Canon van der Paele, 1436, oil on panel, 160 x 124.5 cm (Museum: Groeninge Museum Bruges)

Artists such every bit Jan van Eyck looked carefully at natural and homo-made objects and used oil paint to evoke textures compellingly. New media allowed the product of images in multiples for the first fourth dimension, and the Reformation rocked long-held religious and fifty-fifty political behavior.

Martin Schongauer, Saint Anthony Tormented by Demons, c. 1475, engraving, xxx.0 x 21.viii cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

This chapter focuses on the varieties of media of the then-called Northern Renaissance, especially the invention of printing methods around 1450 that allowed pictures to be produced in multiples rather than one at a fourth dimension. Such an expansion of pictures and information across wider swaths of populations allowed people in Northern Europe to learn about Italian ideas and vice versa. The rate of alter is comparable to the exponential spread of information made possible with the arrival of the digital age. The skilled use of oil paint also allowed Northern artists to create uncanny illusions of reality.

Lucas Cranach, The Police and the Gospel, c. 1529, oil on woods, 82.ii × 118 cm / 32.4 × 46.five in (Herzogliches Museum, Gotha, Germany)

This chapter too focuses on the Lutheran Reformation which began in Wittenberg Germany in 1517, every bit an attack against the corruption of Catholic teaching. Inexpensive, mechanically reproducible media, such as woodcuts and engravings, powerfully dispersed the ideas of the Lutheran Reformation. The Reformation questioned the very legitimacy of religious imagery by proposing that sacred art was a form of idolatry. The Reformation also questioned the authority of the singular church building in western Europe, and motivated the Catholic church to mine the Americas, Asia, and Africa for new members and sources of wealth. For these reasons, didactic oil paintings such as Cranach's various versions of Law and Gospel— the primeval of which date from 1529— also anchored Lutheran ideas in places of public worship, replacing the devotional role of more than traditional altarpieces.

This chapter considers four key problems regarding the Northern Renaissance, beginning with a questioning of the term itself:

- Was there a Northern Renaissance?

- The properties of oil pigment that allowed artists to create illusions of reality

- The influence of mechanically reproducible media (prints)

- The transformational touch on of the Protestant Reformation

Read an introductory essay

The Northern Renaissance in the fifteenth century: an introduction

Read At present

/1 Completed

Was at that place a (Northern) Renaissance?

Traditional timelines show the Renaissance beginning around 1400. The term Renaissance means rebirth, simply what was reborn? According to fifteenth-century scholars (such every bit Leon Battista Alberti) and the wealthy bankers (particularly the Medici in Florence) who supported them, classical antiquity came back to life in the city of Florence. "Classical antiquity" refers to the cultural achievements of aboriginal Greece and Rome. Artists and architects in Italy were geographically closer to the material remains of the aboriginal world, so much Renaissance fine art responded to that proximity. The visual reminders of the ancient world were more sparse North of the Alps. Even though the ruins of Rome were fewer in Northern Europe, at that place was no real belief in a death and rebirth of antiquity. Instead, the site of classical civilisation simply inverse location.

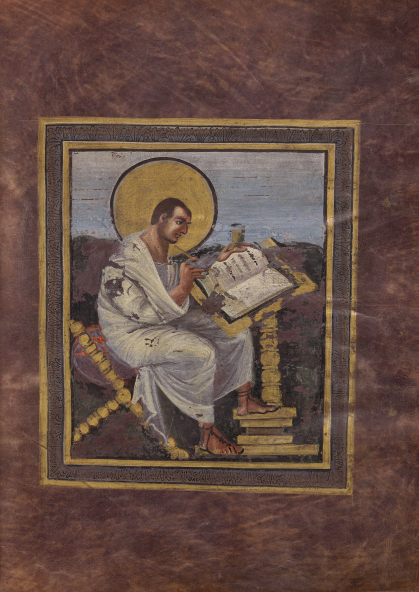

The artists of the Coronation Gospels were interested in the revival of classical styles, which finer linked Charlemagne's rule to that of the quaternary-century ancient Roman emperor Constantine. The classical mode is evident in the pose and clothing of Saint Matthew who recalls images of aboriginal Roman philosophers. Saint Matthew, folio 15 recto of the Coronation Gospels (Gospel Book of Charlemagne), from Aachen, Germany, c. 800–x, ink and tempera on vellum (Schatzkammer, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

After the fall of Rome in the fifth century C.E., the locus of classical learning just shifted North, to be expressed, for instance, in the reign of Charlemagne in the late eight and early ninth centuries. Charlemagne considered himself a Holy Roman Emperor, fifty-fifty though he had started as Frankish chieftain.

Still, the term Renaissance is all-time reserved for Italia, the place for which information technology was invented past scholars. The term "Northern Renaissance," with its Italo-centric tilt, is problematic because information technology makes the contained flourishing of Northern art seem similar a footnote to Italy. However, because art historians share a full general understanding of what information technology means, "Northern Renaissance" is a user-friendly autograph for the flowering of Northern art that occurred while the Renaissance was happening in Italy.

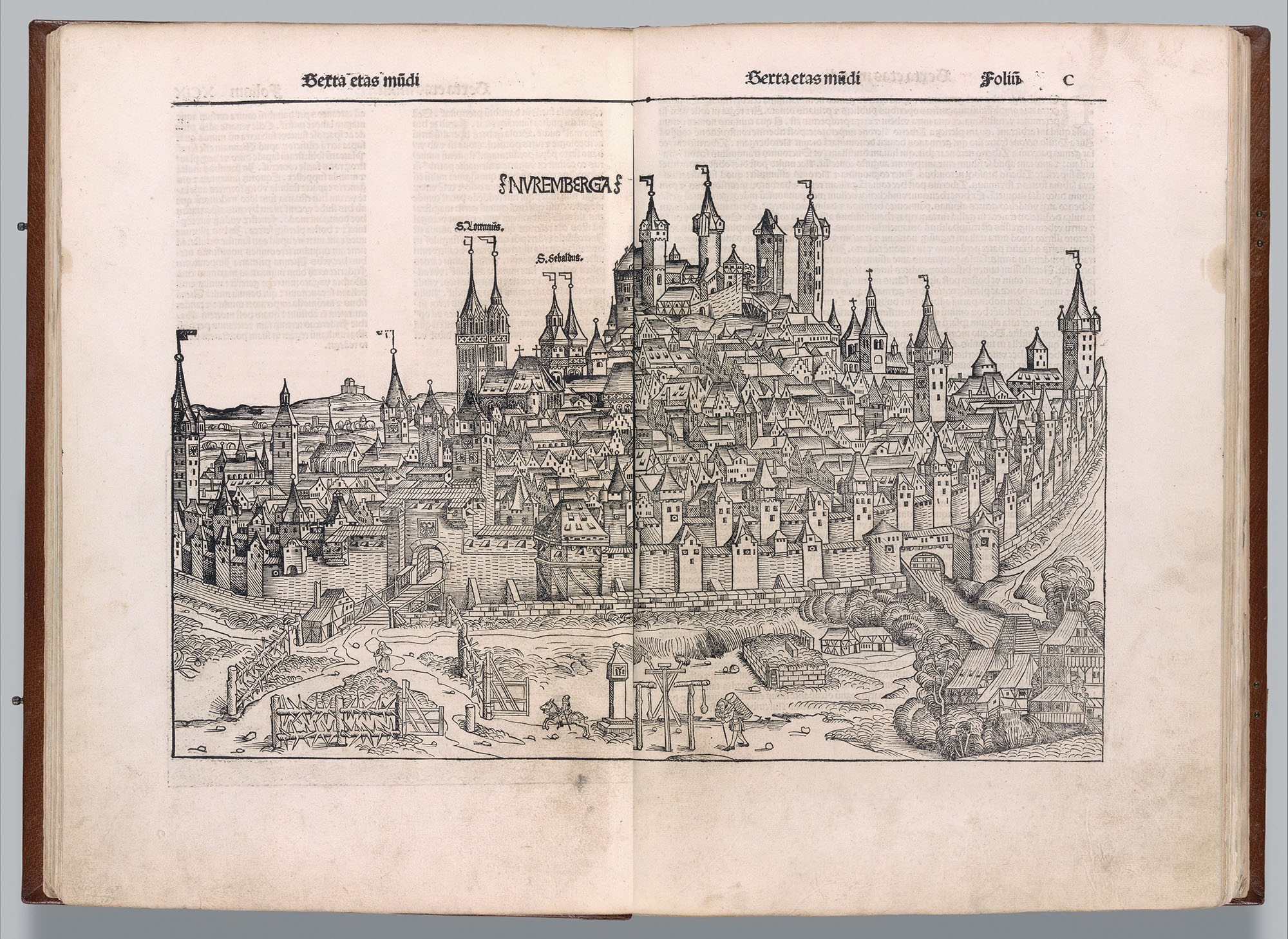

Michael Wolgemut, High german, about 1435–1519, "View of the City of Nuremberg," in The Nuremberg Relate, Nuremburg: Anton Koberger, 1493 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Simple chronological and geographical designators, such every bit "fifteenth-century Bruges" or "sixteenth-century Nuremberg" would be more precise, albeit wordier and less encompassing, and may exist more useful when discussing specific artists or objects. With these provisos in mind, the term Northern Renaissance is still useful, even if it is imperfect.

Renaissance or Early Modern?

Scholars have debated why the Renaissance happened, when information technology started, when it ended, whom it afflicted, and whether or not "Renaissance" is a useful term to depict any of the diverse events of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries anywhere in Europe.

Some scholars use the term "Early Modernistic" to describe the broader changes in civilisation at the cease of the Middle Ages. Though this term is as well flawed and imprecise, information technology is more inclusive and indicates the role the era played in the foundation of the modern and contemporary world with practices such as international trade, colonialism, the continuing shift from agrestal to urban economies, and the exponentially expanded communication made possible through the invention of the printing printing.

Object makers (artists)

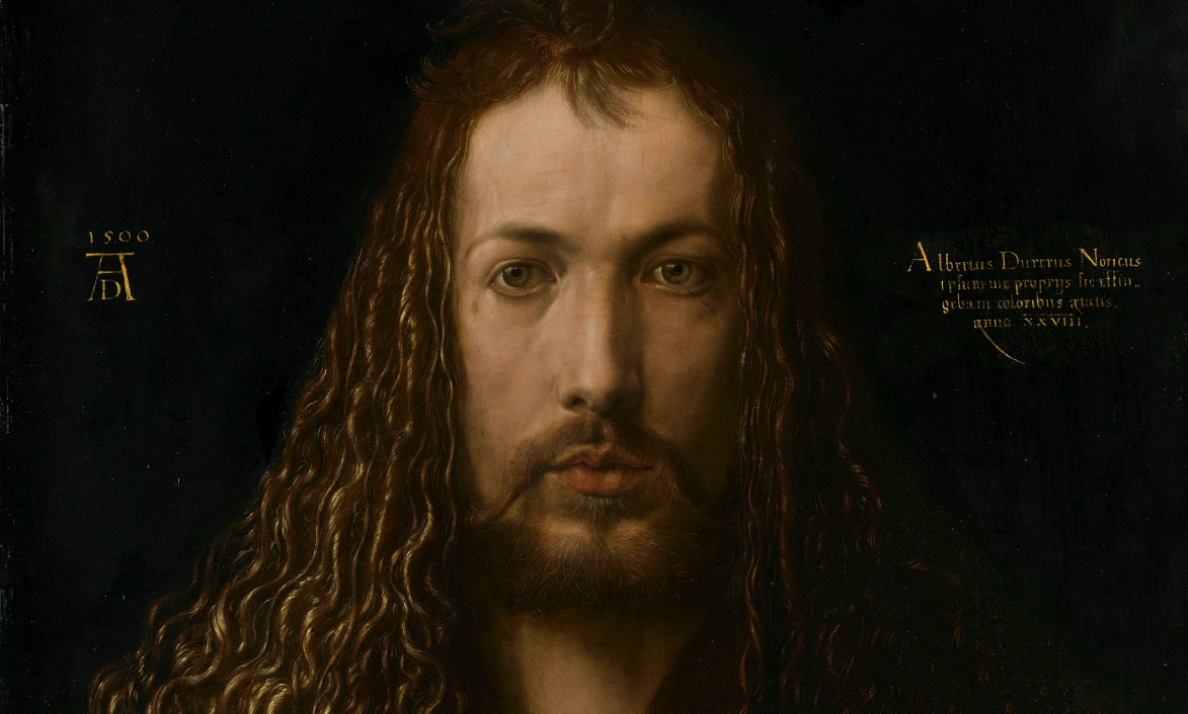

Earlier and even into the Early Modern period, artists were trained craftspeople who worked skillfully but anonymously in workshops nether the authority of a trained master. In the Early Modernistic era, we come across the construction of the idea of a person as a detached individual , rather than primarily equally a member of a social or professional course. This idea is the basis for our familiar stereotype of the artist equally a unique creator of expressive and securely personal works of art, one we often associate with Italian renaissance artists like Michelangelo and Raphael.

Albrecht Dürer, Melencolia I,1514, engraving, 24 x 18.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

This idea flourished in the North every bit well. Albrecht Dürer admired and aspired to the rock-star status of Italian artists. The surpassing verisimilitude of Jan van Eyck's oil paintings and the pathos of Rogier van der Weyden asserted the individuality of Northern artists independent of an involvement in artifact. For instance, today we talk nearly works of art equally "a Michelangelo", "a Raphael" or "a Dürer". The dominance of creative personality marks a shift away from the anonymity of the medieval craftsperson.

Watch videos and read essays about object makers

The role of the workshop in late medieval and early on modern northern Europe: an introduction

Read At present

Albrecht Dürer, Self-Portrait: By taking Christ'south pose, he conflates artist and creator.

Read At present

Albrecht Dürer, Melencolia: In this psychological self-portrait, Dürer captures an imagination paralyzed past inertia.

Read Now

/iv Completed

Oil pigment

One of the most important innovations in the Northern Renaissance was the effective use of oil paint. Though Jan van Eyck did not invent oil paint, he used information technology more effectively than artists before his time. Oil immune artists to paint in layers or glazes that convincingly mimicked the appearance of textures.

Jan Van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434, tempera and oil on oak console, 82.2 x 60 cm (National Gallery, London)

Skin, hair, cloth, foodstuffs, metals, and fabrics glowed with an uncanny-seeming replication of visual feel. Imagine how astonishing the details of the Ghent Altarpiece or the Arnolfini Double Portrait may have appeared to people in the fifteenth century who had never seen a photo!

Watch videos and read essays nigh oil pigment

Jan van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait: This dense and detailed painting does non lack for symbols—or interpretations.

Read Now

Jan Van Eyck, The Ghent Altarpiece: The inner panels are painted in the bold and dynamic naturalistic style for which the artist Jan van Eyck is justifiably famous.

Read Now

/2 Completed

Rogier van der Weyden, The Last Judgment, 1445–50, altarpiece, interior view (Hôtel-Dieu de Beaune)

Altarpieces

Oil paint was often used in Northern Europe to paint many-paneled paintings, known equally polyptychs, which were placed backside the altar tabular array as a backdrop to the performance of the Eucharist, the blessing of the bread and the vino. Such paintings adorning the altar are called altarpieces.

Workshop of Robert Campin, Annunciation Triptych (Merode Altarpiece), c. 1427–32, oil on oak panel, open 64.v x 117.8 cm, central console 64.1 x 63.two cm, each wing 64.5 x 27.three cm (The Cloisters, The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art)

Altarpieces in the fifteenth century often emphasized the humanness of the Christian holy figures equally much as, or even more than, their holiness. Saints, Christ, and the Virgin Mary bled and wept and celebrated just like the viewers who beheld them. Such humanizing bonded viewer and holy effigy and granted viewers admission to holiness via compassion. Empathic identification was the foundation of both small, individual devotional objects that were kept in people'south homes as well, such as the Mérode Altarpiece and more monumental, public objects such as polyptychs.

Sentry videos and read essays about altarpieces and oil paint

The Medieval and Renaissance Altarpiece: an introduction

Read Now

Illustrating a Fifteenth-Century Netherlandish Altarpiece: an introduction

Read Now

Workshop of Robert Campin, Declaration Triptych (Merode Altarpiece): Not only is the level of detail here astonishing, but these everyday objects embody religious symbols.

Read Now

Hugo van der Goes, Portinari Altarpiece: A Northern altarpiece fabricated for a Florentine.

Read At present

/iv Completed

Secular subjects in oil

Artists used oil pigment and mimesis (seeming mimicry of reality) in secular subjects also. Pieter Bruegel the Elder derived the subjects of his art from his responses to the world he lived in, and used oil paint to create a plausible illusion of reality.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Peasant Wedding, oil on canvass, 114 x 164 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

It is imperative, nonetheless, to remember that Bruegel'southward hard-working or hard-partying peasants are not real people but caricatures and types. No motion picture can be an objective transcription of reality or a "scene of everyday life," because all pictures are extrapolations, observations, and interpretations filtered through a person whose perceptions are in turn a product of history. Bruegel and other artists depicted peasants as stand up-ins for human nature, and presented them as bearding stereotypes advisedly bundled in compositions intended to amuse but besides flatter the beholder who was a member of a higher social form.

Watch videos and read an essay about secular subjects in oil

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Hunters in the Snow (Wintertime): What appears to be a aboveboard snapshot of daily life is in fact a finely orchestrated and panoramic vision of the world.

Read At present

Hans Holbein, The Ambassadors: The painting is filled with advisedly rendered details—and an anamorphic skull.

Read Now

/2 Completed

Mechanical Reproducibility and Visual Propaganda

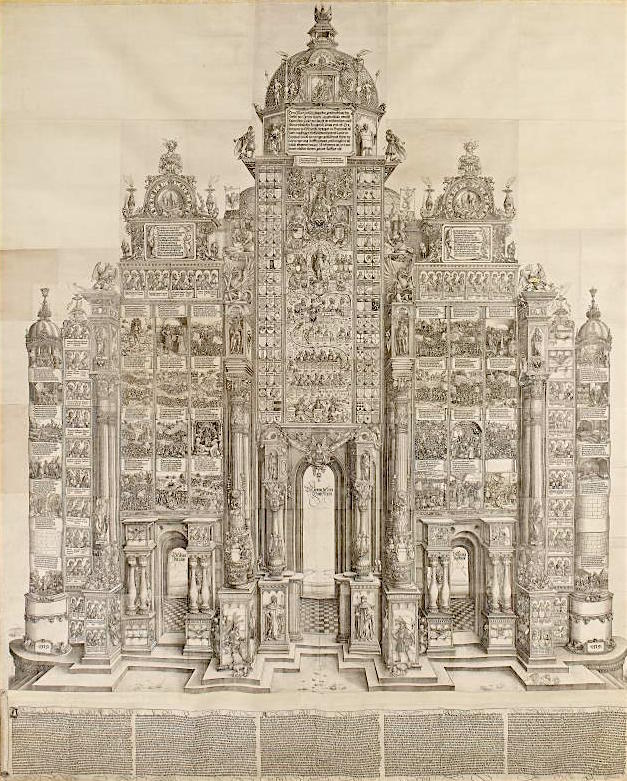

Albrecht Dürer and others, The Triumphal Arch, c. 1515, woodcut printed from 192 individual blocks, 357 x 295 cm, Germany © Trustees of the British Museum

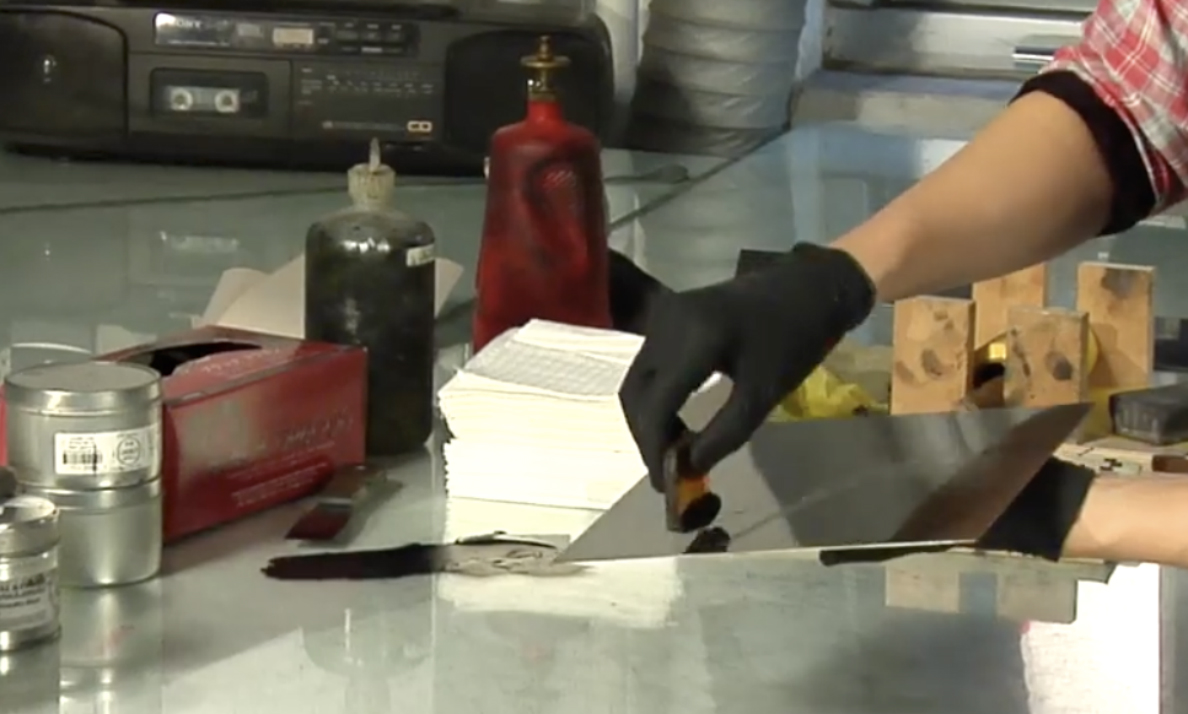

The evolution of mechanically reproducible media such as engravings and woodcuts was every bit life-changing as the advent of photography in the nineteenth century or digital media in the belatedly twentieth. The Northern Renaissance is also the era when books were published with movable type rather than laboriously written by paw. Print technologies arrived in Europe late, as technologies moved from Due east Asia to Primal Asia and finally Europe.

Scout videos and read essays nearly printmaking

Printmaking in Europe, c. 1400−1800: an introduction

Read At present

Introduction to printmaking: an overview

Read At present

Albrecht Dürer, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse: Dürer's skill as a woodcut artist was his ability to conceive such complex and finely detailed images in the negative

Read Now

Albrecht Dürer, Adam and Eve: The engraving ofAdam and Eve of 1504 past the High german renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer recasts this familiar story with nuances of meaning and artistic innovation.

Read Now

/iv Completed

Prints and Protestant Reformation

Printed pamphlets were arguably the engine of the Protestant Reformation, initiated by Martin Luther in 1517. Artists were employed to make Luther'due south theology intelligible to wide swaths of viewers in prints as well as in paintings that were meant to role every bit conceptual blackboards, diagramming the new path to salvation independent of traditional Catholic rituals. Pictures such as Law and Gospel were synthetic to avoid mimesis and emotion in favor of conceptual clarity— even though the intended clarity was not necessarily received as such.

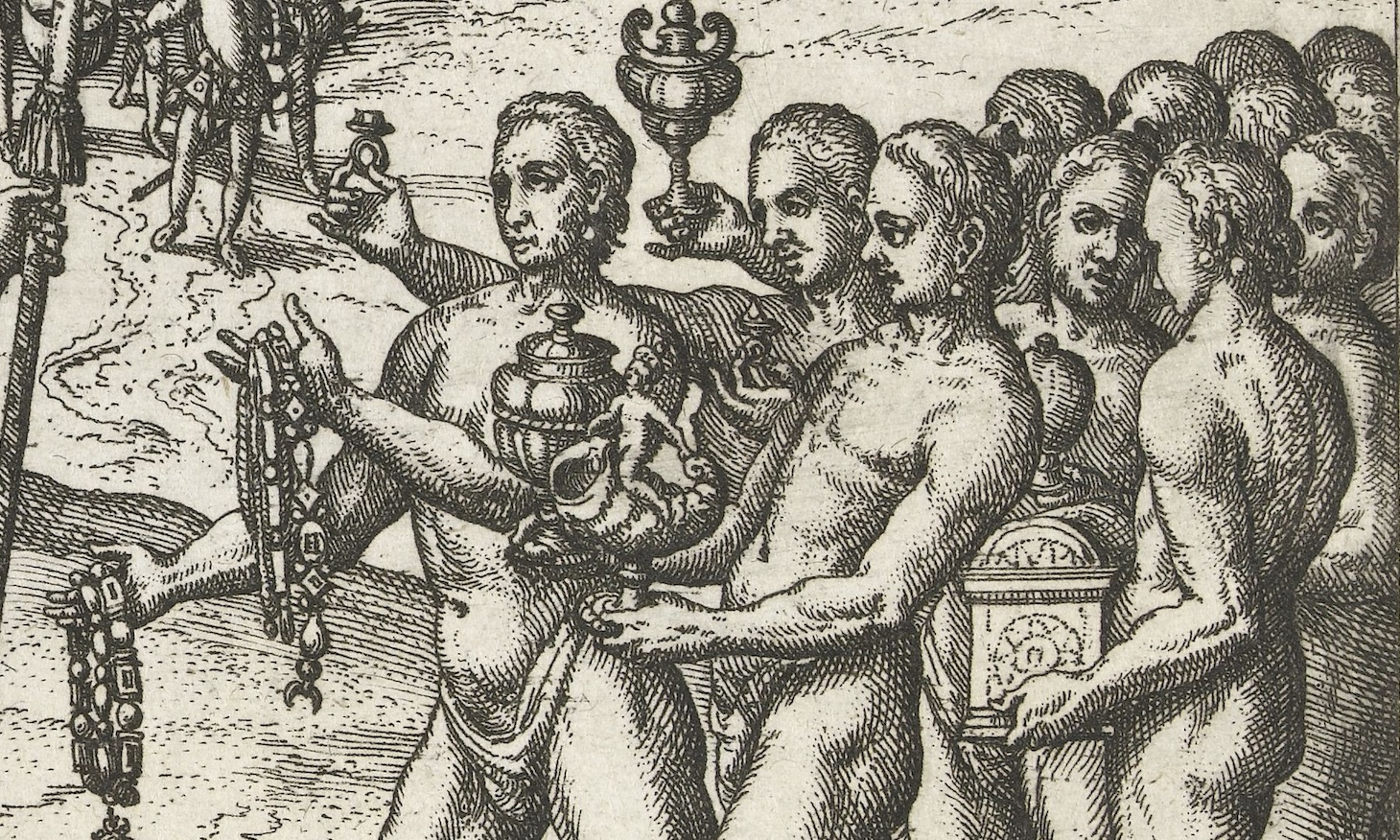

Theodor de Bry, Christopher Columbus arrives in America, 1594, etching and text in letterpress, 18.vi c 19.6 cm (Rijksmuseum)

The affect of the Reformation was felt around the globe. As the Catholic Church lost wealth and members, it turned to the Americas in search of wealth and converts. The founding narrative of the United States reaches back to the arrival of the pilgrims in 1620 or even to the yr before, when the outset shipment of enslaved peoples from Africa arrived, even though Jamestown was founded earlier, in 1607. The pilgrims who sailed on the Mayflower were themselves radical Protestants who believed the Church building of England was not pure enough.

Happily, Albrecht Dürer offers a refreshing alternative to colonialism. His response to an exhibition of Mexica (Aztec) objects when he travelled to the Depression Countries in 1520 is telling.

Dürer, in a letter dated 27 Baronial 1520

All the days of my life I take seen aught that rejoiced my centre then much equally these things, for I saw among them wonderful works of fine art, and I marvelled at the subtle Ingenia of men in strange lands. Indeed I cannot express all that I thought there.

Quoted from Wolfgang Stechow, Northern Renaissance Art, 1400–1600: Sources and Documents (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1989) pp. 100–01.

Watch videos and read essays almost the Protestant Reformation and its effects

The Protestant Reformation: an introduction

Read Now

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Law and Gospel (Law and Grace): The single about influential image of the Lutheran Reformation.

Read Now

Inventing "America" for Europe: Theodore de Bry's engravings assert and assert a sense of European superiority.

Read Now

Theodor de Bry, "Their sitting at meate": De Bry's print presented an English colony every bit chock total of good things to eat and bolt to sell.

Read Now

/4 Completed

Understanding Northern art on its own terms

Albrecht Dürer traveled to Venice twice and returned to Germany enchanted by what he learned about Italian fine art. Pieter Bruegel the Elder traveled across the Alps as far due south as Naples. Dürer, Bruegel, and other artists learned from the triumphs of Italian art and the rejuvenated Italian interest in antiquity. Only the flourishing of print media, oil painting, and religious upheaval that characterized the fifteenth- and sixteenth-century are more of import for understanding Northern art on its own terms.

Oil paintings conveyed a granular verisimilitude unparalleled in other media. Manuscripts (literally, manus-written) gave way to printed books. Mechanically reproducible media created an encompassing visual culture shared beyond geographical limits. Artists achieved a social status equal to their patrons. And the Reformation questioned the very essence of art, in some cases rejecting religious art entirely. Whatever vocabulary nosotros may take at our disposal to describe the art and culture of Northern Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the surviving visual record testifies to the magnitude of alter.

Central questions to guide your reading

Why do some scholars prefer the term "Early Modernistic" to "Renaissance"?

What part does mimesis play in Northern Renaissance oil painting?

What role did impress media play in the advancement of the Protestant Reformation?

Jump down to Terms to Know

Source: https://smarthistory.org/reframing-art-history/printing-painting-northern-renaissance-art/

0 Response to "Northern European Art of the Renaissance Generally Avoided Detail and Texture"

Post a Comment